The awful calamity!

- Extrait de journal : traduction de titres courts

- Visionnage : vidéo sur le canular du zoo de Central Park (1874)

- Compréhension orale et écrite : identifier les raisons, réactions et conséquences du canular

- Culture : le rôle de la presse et la fiabilité de l’information

- Expression orale : présentation en binômes (30 secondes) – “Would this work today?”

- Quiz interactif Kahoot sur les informations de la vidéo

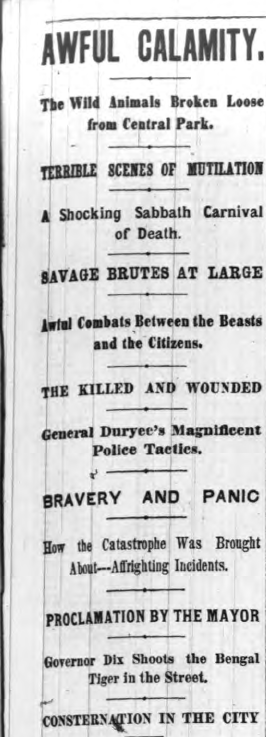

1a. This is an extract from a newspaper in 1874. Read the information about the ‘Awful Calamity’ — copy and translate the titles.

1a. Il s’agit d’un extrait de journal de 1874. Lis les informations sur la « Terrible Calamité » — recopie et traduis les titres.

b. Imagine people’s reactions when reading the news in 1874.

b. Imagine la réaction des gens en lisant les nouvelles en 1874.

Sample answer

Confronted with headlines like “Awful Calamity” and “Sabbath Carnival of Death,” many readers would have spiraled into collective hysteria. The Herald’s authoritative tone and lurid typography lent the story a veneer of credibility, stoking moral panic on a sacred day when shops were shut and rumors spread quickly. People likely imagined apocalyptic scenes—“savage brutes at large,” mangled victims, and desperate police tactics—while a smaller circle of skeptics grumbled about sensationalism and newspaper chicanery.

In practice, citizens might have barred their doors, rushed children indoors, avoided Central Park, and besieged police stations and churches for updates. Some thrill-seekers would have flocked to the streets to corroborate the rumor, while civic leaders prepared proclamations and volunteers braced for heroics—all typical of a city primed for spectacle and anxious about its modern menagerie.

Face à des titres comme « Awful Calamity » et « Sabbath Carnival of Death », de nombreux lecteurs auraient sombré dans une hystérie collective. Le ton autoritaire du Herald et sa typographie tapageuse donnaient au récit un vernis de crédibilité, attisant une panique morale un jour sacré où les commerces étaient fermés et où les rumeurs circulaient vite. On s’imaginait des scènes apocalyptiques — « sauvages en liberté », victimes mutilées, police aux tactiques drastiques — tandis qu’une minorité de sceptiques dénonçait la sensationalisation et la chicanerie journalistique.

Concrètement, les habitants auraient barricadé leurs portes, mis les enfants à l’abri, évité Central Park et pris d’assaut commissariats et églises pour obtenir des nouvelles. Des curieux seraient sortis pour corroborer la rumeur, pendant que des responsables préparaient des proclamations et que des volontaires se tenaient prêts à des actes héroïques — tout à fait typique d’une ville avide de spectacle et anxieuse face à sa ménagerie moderne.

2. Class survey. Do you think the event really happened? 2. Sondage de classe. Penses-tu que l’événement a vraiment eu lieu ?

Class survey — Live results

3. Watch the video and note information about: 3. Regarde la vidéo et note des informations sur :

- The reason for publishing the story.

La raison de la publication de l’histoire. - The reaction of other news publications.

La réaction des autres journaux. - The impact the story had on the zoo.

L’impact que l’histoire a eu sur le zoo.

Sample answer — The reason for publishing the story

The New York Herald later claimed the story was written to draw public attention to the terrible conditions the animals were kept in at the Central Park menagerie. Although this justification came only after the outrage, the paper pretended its goal was to promote reform rather than to shock or entertain readers.

Le New York Herald affirma plus tard que l’article avait été publié pour attirer l’attention du public sur les mauvaises conditions de vie des animaux de la ménagerie de Central Park. Même si cette explication arriva après le scandale, le journal prétendait vouloir sensibiliser le public plutôt que simplement choquer ou divertir.

Sample answer — The reaction of other news publications

Rival newspapers immediately condemned the hoax, calling it “intensely stupid and unfeeling.” The New York Times even reported that outraged citizens went to the district attorney, hoping to press charges against the Herald and its reporter. No legal action was ever taken, but the Herald’s reputation suffered a moral blow in the press.

Les journaux concurrents dénoncèrent immédiatement le canular, le qualifiant de « stupide et insensible ». Le New York Times rapporta même que des citoyens indignés s’étaient adressés au procureur pour tenter de poursuivre le Herald et son journaliste. Aucune poursuite n’eut lieu, mais la crédibilité du journal fut sévèrement critiquée.

Sample answer — The impact the story had on the zoo

The hoax accidentally had a positive long-term effect: it sparked reforms that improved conditions for the animals. The Central Park menagerie began a years-long transformation that eventually led to the creation of the Central Park Zoo. Ironically, the Herald’s circulation also increased thanks to the scandal.

Le canular eut finalement un effet positif à long terme : il entraîna des réformes pour améliorer les conditions des animaux. La ménagerie de Central Park entama une transformation sur plusieurs années qui donna naissance au Zoo de Central Park. Ironie du sort, le Herald vit même son tirage augmenter après cette affaire.

Script — The 1874 Central Park Zoo Hoax

Narrator: In 1874, the New York Herald reported that animals from the New York City menagerie had escaped and were running through the streets on a deadly rampage. What really happened? Let’s dig into this.

Narrator: The New York City menagerie didn’t start out to be a zoo — it just sort of happened. Shortly after construction began on Central Park in the late 1850s, a bear cub was handed to the park’s messenger boy. He had no idea what to do with the cute cub, but decided he would take care of it. Soon, more animals started showing up.

Narrator: Most of the animals were cared for in or around the Arsenal, in what was thought to be a temporary situation. There were no plans in the Central Park blueprints by Frederick Law Olmsted and Calvert Vaux for a zoo.

Narrator: Because of the growing menagerie, the State of New York authorized up to sixty acres of Central Park to be set aside for a zoological garden in 1861. What else could they do?

Narrator: Of course, arguments about where to put the menagerie went on for years, while actual construction turned into a rather ad hoc affair — placing Victorian-style buildings and enclosures wherever they could as more animals arrived.

Narrator: General George S. Custer donated a rattlesnake, while General Sherman gave an African cape buffalo confiscated during his march through Georgia in the Civil War. Charles the tiglon — the rare cub of a male Siberian tiger and a female African lion — was also donated.

Narrator: The public loved the menagerie. By 1873, 7,000 people a day were visiting, and by 1902, annual attendance reportedly reached 3 million.

Narrator: Folks reading the New York Herald on November 9, 1874, were shocked and terrified to read that most of the animals had escaped and gone on a deadly rampage through the city streets. It was described as a calamity and a shocking Sabbath carnival of death.

Narrator: According to the article, a keeper poked a rhinoceros named Pete, who smashed his cage, killed keepers, and set other animals free. The full report was gruesome and described carnage across the city.

Narrator: It mentioned lions, tigers, panthers, an anaconda, and even a sea lion battling a rhino. Police were reportedly shooting animals everywhere and the mayor supposedly ordered citizens to remain indoors.

Narrator: The article immediately caused panic: men armed themselves and reporters scoured the streets for chaos. It was later said the editor of the New York Times ran out waving two pistols.

Narrator: Only readers who made it to the last paragraph learned the truth. “Of course, the entire story given above is a pure fabrication. Not one word of it is true.” The paper claimed the tale was invented by an anonymous reporter while gazing at the cages.

Narrator: Not many had read that far. Rival papers denounced the hoax as “intensely stupid and unfeeling.” Citizens appealed to the district attorney to bring charges, but none were filed. The Herald showed no remorse, arguing the final paragraph made everything clear.

Narrator: A few days later, the paper ran a piece about the menagerie’s poor conditions, implying the hoax was meant to draw attention. For most people, it was too little, too late.

Narrator: Ironically, the outcome proved positive: years of improvements followed, ultimately creating the Central Park Zoo. And the New York Herald didn’t suffer either — its circulation actually grew.

4. React. Do you think this would work today? Justify your answer. (Oral presentation in pairs — 30 seconds) 4. Réagis. Penses-tu que cela fonctionnerait aujourd’hui ? Justifie ta réponse. (Présentation orale en binômes — 30 secondes)